The elbow-joint is a ginglymus or hinge-joint. The trochlea of the humerus is received into the semilunar notch of the ulna, and the capitulum of the humerus articulates with the fovea on the head of the radius. The articular surfaces are connected together by a capsule, which is thickened medially and laterally, and, to a less extent, in front and behind. These thickened portions are usually described as distinct ligaments under the following names: | 1 |

| The Anterior. |

|

The Posterior. |

| The Ulnar Collateral. |

|

The Radial Collateral. |

|

|

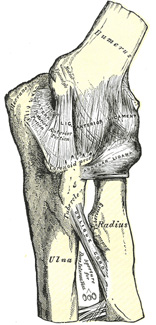

FIG. 329– Left elbow-joint, showing anterior and ulnar collateral ligaments. (See enlarged image) |

| |

|

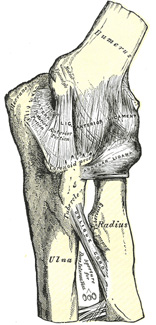

FIG. 330– Left elbow-joint, showing posterior and radial collateral ligaments. (See enlarged image) |

| |

| |

| The Anterior Ligament (Fig. 329).—The anterior ligament is a broad and thin fibrous layer covering the anterior surface of the joint. It is attached to the front of the medial epicondyle and to the front of the humerus immediately above the coronoid and radial fossæ below, to the anterior surface of the coronoid process of the ulna and to the annular ligament (page 324), being continuous on either side with the collateral ligaments. Its superficial fibers pass obliquely from the medial epicondyle of the humerus to the annular ligament. The middle fibers, vertical in direction, pass from the upper part of the coronoid depression and become partly blended with the preceding, but are inserted mainly into the anterior surface of the coronoid process. The deep or transverse set intersects these at right angles. This ligament is in relation, in front, with the Brachialis, except at its most lateral part. | 2 |

| |

| The Posterior Ligament (Fig. 330).—This posterior ligament is thin and membranous, and consists of transverse and oblique fibers. Above, it is attached to the humerus immediately behind the capitulum and close to the medial margin of the trochlea, to the margins of the olecranon fossa, and to the back of the lateral epicondyle some little distance from the trochlea. Below, it is fixed to the upper and lateral margins of the olecranon, to the posterior part of the annular ligament, and to the ulna behind the radial notch. The transverse fibers form a strong band which bridges across the olecranon fossa; under cover of this band a pouch of synovial membrane and a pad of fat project into the upper part of the fossa when the joint is extended. In the fat are a few scattered fibrous bundles, which pass from the deep surface of the transverse band to the upper part of the fossa. This ligament is in relation, behind, with the tendon of the Triceps brachii and the Anconæus. | 3 |

| |

| The Ulnar Collateral Ligament (ligamentum collaterale ulnare; internal lateral ligament) (Fig. 329).—This ligament is a thick triangular band consisting of two portions, an anterior and posterior united by a thinner intermediate portion. The anterior portion, directed obliquely forward, is attached, above, by its apex, to the front part of the medial epicondyle of the humerus; and, below, by its broad base to the medial margin of the coronoid process. The posterior portion, also of triangular form, is attached, above, by its apex, to the lower and back part of the medial epicondyle; below, to the medial margin of the olecranon. Between these two bands a few intermediate fibers descend from the medial epicondyle to blend with a transverse band which bridges across the notch between the olecranon and the coronoid process. This ligament is in relation with the Triceps brachii and Flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar nerve, and gives origin to part of the Flexor digitorum sublimis. | 4 |

| |

| The Radial Collateral Ligament (ligamentum collaterale radiale; external lateral ligament) (Fig. 330).—This ligament is a short and narrow fibrous band, less distinct than the ulnar collateral, attached, above, to a depression below the lateral epicondyle of the humerus; below, to the annular ligament, some of its most posterior fibers passing over that ligament, to be inserted into the lateral margin of the ulna. It is intimately blended with the tendon of origin of the Supinator. | 5 |

| |

| Synovial Membrane (Figs. 331, 332).—The synovial membrane is very extensive. It extends from the margin of the articular surface of the humerus, and lines the coronoid, radial and olecranon fossæ on that bone; it is reflected over the deep surface of the capsule and forms a pouch between the radial notch, the deep surface of the annular ligament, and the circumference of the head of the radius. Projecting between the radius and ulna into the cavity is a crescentic fold of synovial membrane, suggesting the division of the joint into two; one the humeroradial, the other the humeroulnar. | 6 |

| Between the capsule and the synovial membrane are three masses of fat: the largest, over the olecranon fossa, is pressed into the fossa by the Triceps brachii during the flexion; the second, over the coronoid fossa, and the third, over the radial fossa, are pressed by the Brachialis into their respective fossæ during extension. | 7 |

| The muscles in relation with the joint are, in front, the Brachialis; behind, the Triceps brachii and Anconæus; laterally, the Supinator, and the common tendon of origin of the Extensor muscles; medially, the common tendon of origin of the Flexor muscles, and the Flexor carpi ulnaris. | 8 |

| The arteries supplying the joint are derived from the anastomosis between the profunda and the superior and inferior ulnar collateral branches of the brachial, with the anterior, posterior, and interosseous recurrent branches of the ulnar, and the recurrent branch of the radial. These vessels form a complete anastomotic network around the joint. | 9 |

| The nerves of the joint are a twig from the ulnar, as it passes between the medial condyle and the olecranon; a filament from the musculocutaneous, and two from the median. | 10 |

| |

| Movements.—The elbow-joint comprises three different portions—viz., the joint between the ulna and humerus, that between the head of the radius and the humerus, and the proximal radioulnar articulation, described below. All these articular surfaces are enveloped by a common synovial membrane, and the movements of the whole joint should be studied together. The combination of the movements of flexion and extension of the forearm with those of pronation and supination of the hand, which is ensured by the two being performed at the same joint, is essential to the accuracy of the various minute movements of the hand. | 11 |

| The portion of the joint between the ulna and humerus is a simple hinge-joint, and allows of movements of flexion and extension only. Owing to the obliquity of the trochlea of the humerus, this movement does not take place in the antero-posterior plane of the body of the humerus. When the forearm is extended and supinated, the axes of the arm and forearm are not in the same line; the arm forms an obtuse angle with the forearm, the hand and forearm being directed lateral-ward. During flexion, however, the forearm and the hand tend to approach the middle line of the body, and thus enable the hand to be easily carried to the face. The accurate adaptation of the trochlea of the humerus, with its prominences and depressions, to the semilunar notch of the ulna, prevents any lateral movement. Flexion is produced by the action of the Biceps brachii and Brachialis, assisted by the Brachioradialis and the muscles arising from the medial condyle of the humerus; extension, by the Triceps brachii and Anconæus, assisted by the Extensors of the wrist, the Extensor digitorum communis, and the Extensor digiti quinti proprius. | 12 |

|

FIG. 331– Capsule of elbow-joint (distended). Anterior aspect. (See enlarged image) |

| |

|

FIG. 332– Capsule of elbow-joint (distended). Posterior aspect. (See enlarged image) |

| |

| The joint between the head of the radius and the capitulum of the humerus is an arthrodial joint. The bony surfaces would of themselves constitute an enarthrosis and allow of movement in all directions, were it not for the annular ligament, by which the head of the radius is bound to the radial notch of the ulna, and which prevents any separation of the two bones laterally. It is to the same ligament that the head of the radius owes its security from dislocation, which would otherwise tend to occur, from the shallowness of the cup-like surface on the head of the radius. In fact, but for this ligament, the tendon of the Biceps brachii would be liable to pull the head of the radius out of the joint. The head of the radius is not in complete contact with the capitulum of the humerus in all positions of the joint. The capitulum occupies only the anterior and inferior surfaces of the lower end of the humerus, so that in complete extension a part of the radial head can be plainly felt projecting at the back of the articulation. In full flexion the movement of the radial head is hampered by the compression of the surrounding soft parts, so that the freest rotatory movement of the radius on the humerus (pronation and supination) takes place in semiflexion, in which position the two articular surfaces are in most intimate contact. Flexion and extension of the elbow-joint are limited by the tension of the structures on the front and back of the joint; the limitation of flexion is also aided by the soft structures of the arm and forearm coming into contact. | 13 |

| In any position of flexion or extension, the radius, carrying the hand with it, can be rotated in the proximal radioulnar joint. The hand is directly articulated to the lower surface of the radius only, and the ulnar notch on the lower end of the radius travels around the lower end of the ulna. The latter bone is excluded from the wrist-joint by the articular disk. Thus, rotation of the head of the radius around an axis passing through the center of the radial head of the humerus imparts circular movement to the hand through a very considerable arc. | 14 |